Interviews • 23 May 2019

Madame Genta on Gérald Genta’s Legacy

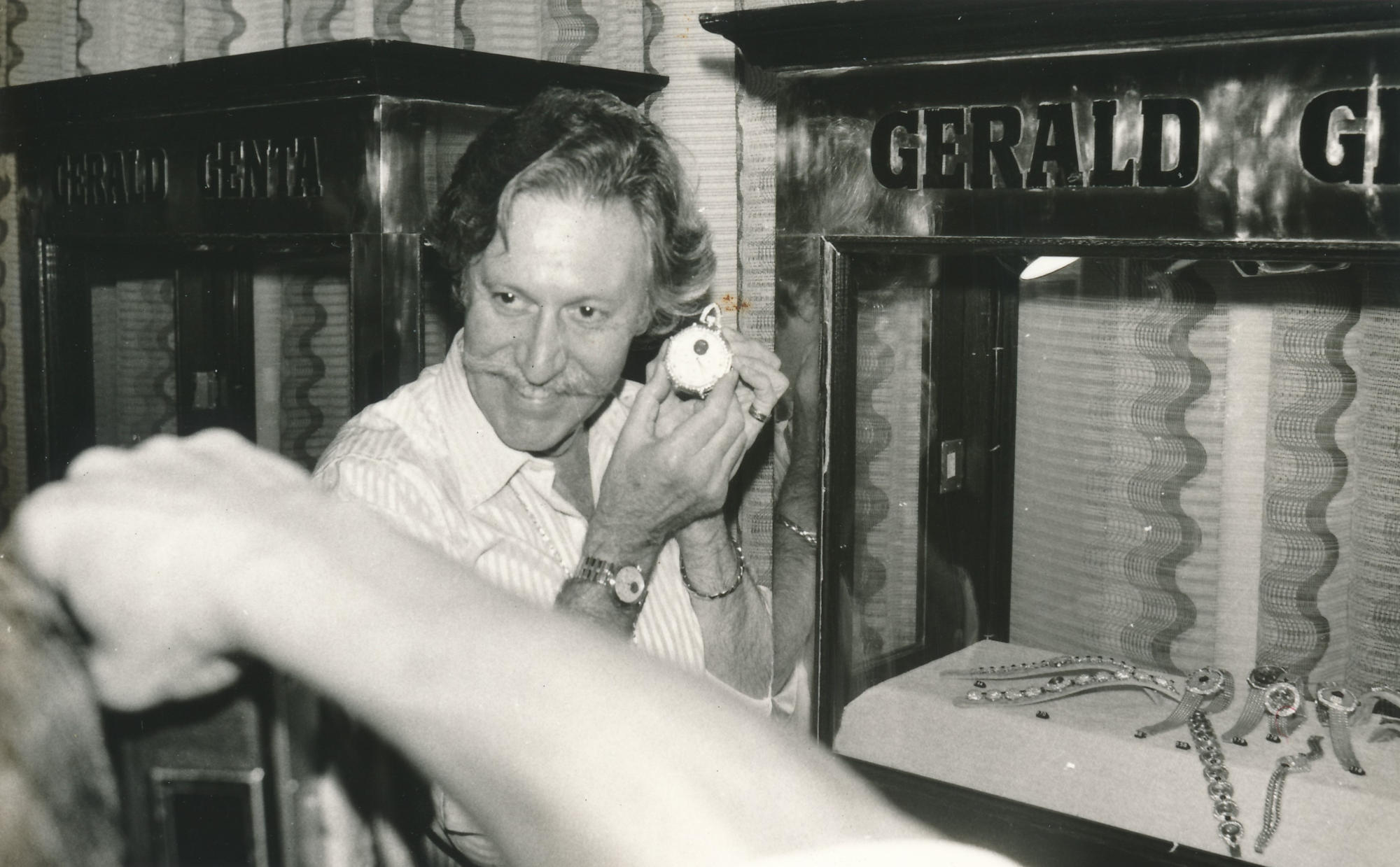

From the Royal Oak to the Nautilus, Gérald Genta’s legacy is inextricably tied to many of today’s cult classics. Having designed so prolifically throughout his career – we’re talking upwards of 100,000 designs – a look at his design philosophy and artistic career is much deserved. Especially so considering the founding of the Gérald Genta Heritage Association earlier this year.

Led by Madame Genta with a panel that reads like the who’s who of the watch industry, the Gérald Genta Association celebrates Genta’s ground-breaking career and enduring influence on the industry. It also aims to promote and support the next generation of up and coming watch designers. I was fortunate enough to have had a chat with Madame Genta earlier this year on all things relating to Gérald Genta and how the Association aims to further promote his legacy.

Why Watches?

Because he was Swiss he designed watches. He said if he’d been Italian, he would have designed cars, if he’d been born French he might have gone into fashion. He was more than a designer; he was an artist. Some are first designer then artist. He was an artist first and designer afterwards and applied his art to watches. But he could have applied it to anything.

He loved cars, he kept saying that if he been able to do that, he would have bought a Ferrari Daytona, not to drive it, but to put it on a turntable in his sitting room because it was the most perfectly designed car.

And this was reflected in the design process, he’d paint each design?

Oh yes very much so. Very very much so. Because for him, he never looked at watches as just watches, it was a means of applied art really. It’s not surprising that it was in Singapore that they called him the Picasso of watches. Because in a way it made sense, to him that’s what he was.

He was re-positioning watches as wearable art.

That’s it, he never felt – I mean he died in 2011 – but he never felt threatened by phones or technology. Because he said you wouldn’t need to tell the time because you have a phone or an Apple watch or whatever, but that will not hurt the beautiful watch market. And he was right.

What was his inspiration? Did he look at the industry for inspiration or look beyond our world of watches?

He never looked at other people’s watches and in fact, he used to tell young designers “do not look at other watches, look at nature”. So, his obsession was that you do not look at the Swiss book of watches, you look at nature, you look at architecture and everything else and somehow it will come back into your own creation. He was obsessed with that.

After a while that process, it’s not even conscious. It’s so ingrained….

That’s what he said, you are so right. He said it came spontaneously. He designed every single day and every design was painted with fine brushes.

Was it a fluid or focused process?

Very fluid. He would go to his desk. He would start with a circle that he would do with his compass, and then he would go from there. I always told him how do you know what you want to design, and he said “it comes to me”. It was quite incredible.

He seemed to paint more prolifically later in his career. Painting not just watches but self-portraits for example.

He became more abstract. But always for him, it was about colours. In the factory let’s say when somebody wanted rubies on a watch, no one was able to choose the rubies to use. It had to be him; he had the eyes. He loved colours, so later in life, he painted more abstract but always always with a lot of colours. He would start designing watches, I’m talking at 6 o’clock in the morning, until lunchtime. Then we would have lunch and in the afternoon he would paint. And it was quite a routine.

Do you think one of the main reasons why his designs are so enduring, is that they’re more a product of human and artistic expression? The quest to make beautiful things is timeless.

I really think so. You know Gérald would go into a room, anywhere, and he’d come out and say “did you notice the way the fireplace was carved, the table”. He took all that in. You know he wasn’t going around at Baselworld or SIHH looking at every window, he wasn’t particularly interested in that.

I’ve seen some of the paintings. The designs are just as beautiful as the watches, the thoughtfulness and the clarity…

They are. The idea is that we’re going to have an exhibition. It will be an exhibition on wristwatches, and he will be a central part of it. And we will be exhibiting his designs. Because there are thousands of designs, nobody has ever seen. Ever!

I think it’s the perfect way to really inspire the next generation, you need source material to look at and be inspired by.

And you know it’s nice for me to have kept this relationship going over 35 years, it means a lot, it’s like bringing all the threads back together….

Michael means so much to us, I mean The Hour Glass means so much to us, you know we sort of grew together at the very very beginning, we met them [the Tay family] when they first opened at Lucky Plaza. Michael was at our wedding and we’ve been close ever since.

During those initial years when you met the Tay family, how did that come about?

Gérald went to Singapore, went to Lucky Plaza and showed his watches, he had like six or seven and they fell in love with it. They were the first ones to put on an exhibition for him. Then when I married him, they also organised for us a Malay wedding, so I married him nearly sort of twice, there’s a lot of links you see, a lot of history and it means a lot. I remember going to Kuala Lumpur and they organised a proper Malay wedding.

We had got married like 3 weeks before when they had come to Monaco and then we got married again. I used to tell Jannie and Henry I can never get rid of him can I – now that I’ve married him twice {laughs}. And the Tay’s got Gérald straight away, they understood him straight away. It was brilliant for us and brilliant for them, it was the best association ever and we sailed through all these years together.

How was the watch culture back then in Asia?

You were seeing a lot of the Sultans of these different states who really were looking for one-off pieces. And Gérald, at the end of the day was sort of a maker of prototypes, because every Sultan or the wife of the Sultan, or family member wanted something unique. So that is what also encouraged this constant creativity because it was always a one-off. Other brands if they’d had one of these watches, they’d further scale up production and would have a best seller. That is why I have all these designs, that can be best-sellers. They were one-offs because he was able to produce another one the next day. And I’d say, “so which one do you prefer?” and he used to say “the one I will design tomorrow”.

Did he enjoy the look on the face of these collectors when their watch arrived?

Oh, he loved that. There was an Italian guy who said when he gave him a beautiful watch, this watch will keep me company. Which was lovely. There was a client who didn’t hear very well, he was a bit deaf, so for him he created a minute repeater where the case was thinner and the donged in a way so that sound would come out louder, so when he brought that to him in New York, he had tears in his eyes. There were some very special moments. These moments he lived for. He didn’t live for marketing. No. But these very cherished clients still exist and phone me to this day.

They understood why he was so special.

That satisfaction, you know. This is your creation, and someone is getting it, understanding it and loving it. It’s wonderful.

And then you look at some of his other designs which were scaled up and how they brought just as much satisfaction to many many collectors.

Not only are they perfect but they can be manufactured. You see you have designers who design wild dreams, which are beautiful but cannot be manufactured. Every one of his designs can be taken to a factory and it is designed in a way that all they need to do is reproduce it.

It’s one of the hardest things to achieve…

It is. Because you do have these amazing people but at the end of the day the thing remains a dream. He knew how to design it and how to manufacture it. For the Royal Oak, for instance, he followed the process of manufacturing at Audemars Piguet every step of the way. Telling them that this is how you do the dial for example. That makes a big difference.

He tended to have an affinity for octagonal shaped watches. Was that something he often talked about?

Absolutely. He loved it. To him, it was the perfect circle with an octagonal case. And if you look at my wedding ring, my wedding ring is octagonal. Of course, the 8 in Asia for good luck, but he loved that shape. If you came to our house you will see that some of our side tables are octagonal, it was definitely his favourite shape.

It goes back to what you were saying earlier how he took inspiration from nature. Certain rock formations are octagonal in shape or like how honeycomb is hexagonal

That’s it. That’s exactly what he said. To him it was perfect. And you know he started with what we can call quite a hard octagon with the Royal Oak, it’s quite a sharp octagon. And then the Genta one (under the Genta line) was softer and there is one that hasn’t been seen which part of the new generation of octagons that he was working on.

Speaking of the next generation, it’s fantastic to see what the Association is doing to keep Gérald Genta’s legacy going.

No one else was doing what he was doing. So, we’re just following in his footsteps. Everyone on the board has been chosen for their integrity, for their knowledge and their passion. It’s very important for the next generation to be involved and to take over.

For more on the Association head over to https://geraldgenta-heritage.com/en/