Collector’s Guides • 16 Aug 2019

Patek Philippe Rare Handcrafts

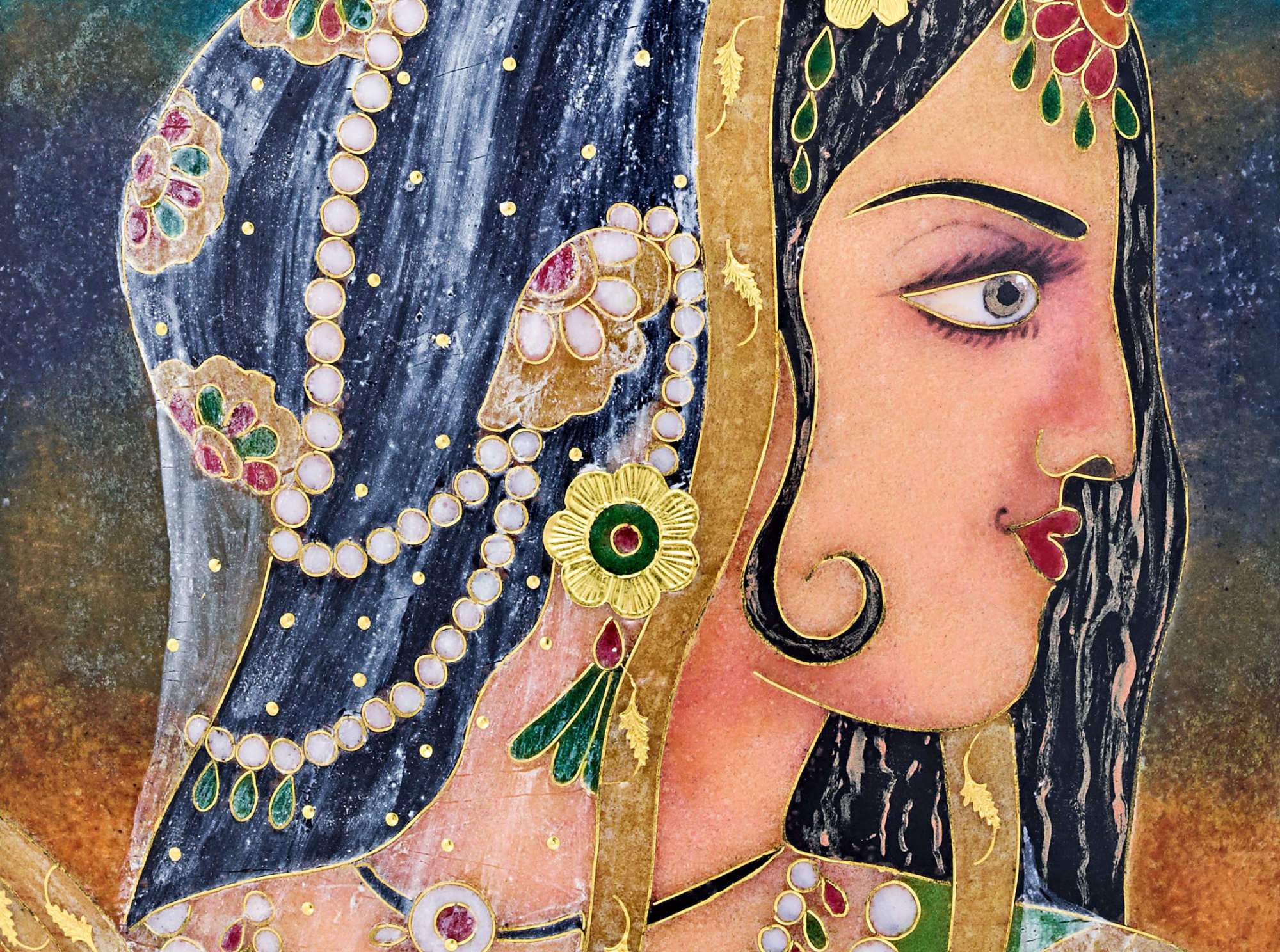

Patek Philippe’s Rare Handcrafts range is somewhat elusive: apart from the fact that only a very few number of pieces are made, and perhaps predicated on it, very few are accessible to reviews by journalists, or admiration and ownership by the public. I have had the privilege of handling a number of these; most memorably the Calatrava ref. 5077P “Scarlet Macaw” and “Blue-and-Gold Macaw”, the entire dials of which frame a portrait of the magnificent New World beauties. What is so remarkable about these is the flawlessness of execution; under a loupe with fifteen-fold magnification, no shortcomings are to be found. The colours and the nuances of shade are representative of their plumage in real life; the sheen of the corneas uncannily real.

But it is not only in the domain of ornithological tribute that Patek Philippe has demonstrated its enamelling prowess; that being said, the ref. 5089G “Gouldian Finch” is another immensely beautiful piece from the Rare Handcrafts collection that I have personally examined. If you are not yet convinced of how exemplary Patek’s enamelers are, a quick visit to their YouTube page and the resolution of their videos on the Rare Handcrafts range may just persuade you. Despite having handled these pieces in my own accord, watching the process of this excruciatingly difficult endeavour – short of visiting the artists – invites a considerable amount of appreciation.

Enamelling has been a long-held Genevan tradition: the bloody deracination of Protestant Huguenots from France by King Charles IX, incited by his mother Catherine de Medici, known as the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre of 1572, led to their influx to the much more religiously hospitable lands of Calvinist Geneva. A similar drain of French Calvinist Protestants, which included skilled jewellers and watchmakers, occurred in 1685 when the Edict of Fontaineblaeu (the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, which had permitted the Huguenots to practice their religion without state persecution) was signed by Louis XIV.

Analogous to Antoni Patek’s exile from Poland and subsequent settlement in Geneva in 1835, these French exiles carried with them their dexterity in gem-setting, painting, and enamelling – however, given the strict Calvinist milieu in their new domicile, which discouraged ornamental expression and the use of jewellery – they turned their attention to watchmaking.

Royal Clientele

From the earliest days of this watchmaker’s history, when Antoine Norbert de Patek and his then-partner, François Czapek joined forces in Geneva in 1839 (six years before the arrival of Jean-Adrien Philippe), offering an undecorated hunter-cased pocketwatch (that is, a watch case with an additional, cuvette caseback) would have been unthinkable; beginning with elaborate engraving, which was informed by their Polish history, the first enamels followed in quick succession – allusions to masterpieces from significant artistic movements, and finally, miniature portraits, most notably a series of watches dedicated to royal clientele.

It was at the Great Exhibition held in London at the behest of HRH Prince Albert, showcasing 19th-century breakthroughs – from the electric telegraph to the hydraulic press to the keyless watch – that Patek, Philippe & Cie. exhibited the latter, featured in an elaborately-finished pendant watch, one of two purchased by Queen Victoria, who had also purchased a repeating gold-cased chronometer for her husband.

The primary attraction of Her Majesty’s pendant watch was not the caseback, which featured a bouquet comprised of rose-cut diamonds set in lapis-blue enamel, but a much more discreet facet of the watch, denoted by “Invention Brêvetéé” on the cuvette, that nonetheless was a very important development in the functional utility of the pocketwatch.

Patek had met Philippe at the Exposition des produits de l’industrie français, or, “Products of Industry Exhibition”, in 1844; the latter was a watchmaking prodigy and son of a French watchmaking autodidact, who propounded the benefits of a keyless winding system. Patek noted the promise of the idea, which made redundant the separate key for winding one’s watch, which until then had been the norm. It was easy to misplace, and the keyhole of which permitted the ingress of water and dust – Philippe’s invention of the modern winding crown permitted the user to manipulate his or her watch with as simple a process as “push to wind; pull to set”, and enabled the possibility of designing cases to be more water-resistant.

Bastion of Genevan Craftsmanship

Patek Philippe has long been at the forefront of innovation, as it demonstrated with the winding-stem, but it has also long taken upon itself to be the guardian of tradition and the bastion of the finest Genevan craftsmanship. The popularity of enamel has ebbed and flowed with time, and it was in the Sixties that it reached a point of near-desolation: extraordinaire Suzanne Rohr, one of the great enamellers of the 20th-century, who herself was obliged to forgo her particular talent and join an advertising agency as a graphic designer, recounts the decline of this craft. Thankfully, by a serendipitous stroke of luck, Rohr was introduced to Henri Stern, and her legacy is perpetuated today by Anita Porchet, who is regularly commissioned by Patek Philippe for its Rare Handcrafts novelties.

The latitude of this guide does not permit extensive coverage of the processes involved in producing such pieces; nonetheless, I trust a brief introduction to the various means of savoir-faire at Patek Philippe will pique your interest.

Wood Micro-Marquetry

Wood micro-marquetry is the artistic usage of wood veneers to create a work of art: as exemplified by this 5077P “Royal Tiger” wristwatch, the grain and tint of each species of wood is employed to represent a natural object, as seen in this incredibly lifelike representation of the Bengal tiger, where the direction of the grain corresponds to the natural nap of its fur. Patek Philippe pioneered this novel technique in 2008, having had previous experience in marquetry, but simply not on this scale, on surface areas scarcely three centimetres across.

Artistry of Enamelling

Enamel craft involves the usage of crushed silica sand (known as fondant; it is transparent), and having been combined with water to form a paste, can be coloured with metal oxides. The paste is applied to a surface that has been meticulously cleaned and is left to dry. It is then fired in a kiln at approximately 850 degrees Celsius, fusing to its metal base. Depending on its intricacies, a model may be returned to the kiln for up to twelve times. Enamel is admired for its unchanging properties, being unaffected by UV radiation and often found in the same condition as it was created, unchanged after decades, if not centuries of wear.

Cloisonné

Cloisonné is an additive technique; a fine wire, usually gold, is bent into segments to form a design and is affixed to a base plate. Multiple segments, or cells, may be created with this fine wire; filled with enamel, they may be fired successive times, depending on the colour, type of enamel used, and the desired play of transparency and depth.

Champlevé

Champlevé is a reductive technique; the cells are engraved beforehand, which are then filled with enamel, and fired in a similar process to that of cloisonné enamel.

Pailonné

Pailonné involves the usage of diminutive pieces of gold leaf, called paillons, which are embedded in layers of transparent enamel.

Miniature Painting

Miniature painting is the final, and rarest technique; it is distinct from the rest from the outset, where fondant is mixed with oil, and not water. It is applied with a very fine brush (sometimes, as fine as a single strand of human hair) on a ground layer of enamel and fired. Patek Philippe has magnificently represented portraits, landscapes, natural objects, and great works of engineering and art in the most identifiable manner by this technique.

Final Thoughts

An accomplished collector has said in an interview, “For the more discerning buyers, go for the rare handcrafted pieces. Many don’t understand how Patek Philippe is keeping their traditions alive in craftsmanship like enamel, guilloche, and so forth. If you are able to get your hands on a piece from the Rare Handcrafts collection, consider yourself very fortunate as these pieces normally sell out.”

Patek Philippe expresses its best (and the world’s best) technical prowess in the Grand Complications; it has demonstrated its unrivalled artistic finesse in the Rare Handcrafts. With the Rare Handcrafts line comprising the most exquisite table clocks, pocketwatches, and of course wristwatches, the special pieces to be released for the 2019 Grand Exhibition in Singapore are to be highly anticipated.

[Editors Note: In the lead-up to the 2019 Patek Philippe Watch Art Grand Exhibition David wrote a series of articles covering the gamut of watches Patek Philippe makes, including: Part 1 The Calatrava, Part 2 Patek Philippe Rare Handcrafts, Part 3 The Patek Philippe Nautilus, Part 4 The Patek Philippe Aquanaut, Part 5 The Patek Philippe Complications and Part 6 The Patek Philippe Grand Complications]

Patek Philippe Watch Art Grand Exhibition in Singapore

Running from the 28th of September until the 13th of October Patek Philippe will be hosting the Watch Art Grand Exhibition at the Sands Theatre (Marina Bay Sands). Taking place during the Singapore Bicentennial year, the Grand Exhibition underlines the importance of Singapore and Southeast Asia for Patek Philippe. These markets are not only significant when it comes to the numbers of collectors and enthusiasts based in the region, they also play a major role in building an appreciation for the work of fine mechanical watchmaking. For more information click here.