Cultural Perspectives • 23 Oct 2015

The Art Of Guilloché In 3 Questions

“Guilloché work: extremely varied pattern of crossing or interlaced lines, giving a decorative effect. Guilloché work is no longer in fashion”.

This delicious definition comes from the Berner, the historic unofficial dictionary of watchmaking, written in 1961 – hence this note by Mr Berner himself: “guilloché work is no longer in fashion”!

What is it?

More than half a century later, such a statement would probably make the watchmaking world smile indulgently: more than ever before, guilloché is now a must on high-end watches – and on affordable ones, too. However, the legendary pattern still carries strong associations with Swiss manufactures such as Breguet. Recently, independent watchmakers have also started using guilloché as one of their hallmarks.

Who uses it?

Today, Vacheron Constantin is considered as the first watchmaker to have made guilloché pocket watches. A few years later, around 1786, Abraham-Louis Breguet also began fitting his watches with engine-turned silver or gold dials of his own design. Under him, guilloché became an art form, with hand-engraved lines and hollowed-out the areas of the dial reserved for indications such as the power reserve, the moon’s phases, the subdial for the seconds, and so forth. A first set of patterns was born: clou de Paris hobnailing, pavé de Paris cobbling, sunburst, barleycorn, waves, cross-weave, checkerboard, flame, and many more. Today, the same kind of engine-turned guilloché work is also carried out on plates made of mother-of-pearl.

Every year, Vacheron Constantin creates a Métiers d’Art collection that uses guilloché in many instances. Here, the watch features different figures thanks to a combination of the arts of engraving, enamelling and guilloché work, playing on depth and mirror-like effects.

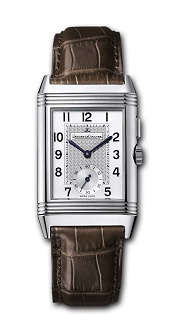

Now, however, independent brands have invented new forms of guilloché. For instance, Audemars Piguet’s “tapisserie” pattern on its Royal Oak collections has become well-known. Kari Voutilainen is another master of guilloché, as seen on Parmigiani Fleurier’s Transforma CBF. Breitling has redesigned its Chronomat collection; the latter features a square guilloché pattern on the dial. And no one could conceive of Jaeger-LeCoultre’s legendary Reverso without its central rectangular guilloché.

How’s it done?

Traditionally, guilloché is done by hand on a large, specially designed machine, built to multiply human strength so as to carefully chisel tiny pieces of gold or silver off the plate, thus creating the desired pattern. The guillocheur turns a crank which allows the piece to be rotated and decorated, and also advances the carriage on which the cutting tool travels, cutting the fine and regular features into the material.

Nowadays, most guilloché patterns are made by robots: the ubiquitous CNC machining, now used in all watchmaking companies. During the course of the twentieth century, with the advent of industrial techniques, hand craftsmanship carried out piece by piece was partially replaced by modern methods. Automatic machines, stamping and, more recently, CNC have emerged, allowing larger numbers of parts to be produced for less. Such methods are suitable for mass production, but do not allow for any customization; the latter remains the preserve of traditional hand engravers. That said, specialized companies and artisans guillocheurs are now endangered species. Traditional guilloché is pure craftsmanship. There is no dedicated training school, and the special machines are no longer being made.