Interviews • 05 Jun 2020

James Palmer on Aiming For Independence

After graduating from the British School of Watchmaking, James Palmer headed over to the Isle of Man to work with famed independent watchmaker Roger W. Smith. Unlike most of his classmates who pursued careers with the large watch groups, James set his sights on a career as an independent watchmaker. We recently caught up with James to talk about how he serendipitously got into watches, his journey thus far and his horological ambitions.

To kick things off, if you can tell us about how you got into watchmaking. I believe you had an epiphany while watching Netflix?

So yeah, basically in 2016, I was in college, I was 18. And I was just studying my A Levels and I was kind of hating it, I was just wasn’t taking it seriously. I was kind of mooching off. One day, around this time, I was scrolling through Netflix looking for something to watch, and I saw this film called the Watchmakers Apprentice. The name intrigued me. I didn’t really know what it was, so I clicked on it and gave it a watch and it just kind of just sparked something in my head. I don’t know what happened, but I do know that Roger’s story really resonated with me. How I was feeling at the time, it seemed that’s how Roger felt earlier on.

Roger said he hated the traditional school system and didn’t really get along well with it and it didn’t make sense to him. That was the same with me. So, after watching that, I instantly scoured online – doing research on where you can study watchmaking, seeing if I could do it here in the UK. And so, a few hours later I applied to the British School of Watchmaking. I was invited to do a bench test; it was like an assessment day type of thing which involved a maths test and a few other bits and bobs. And then weirdly enough I got accepted!

Some people have a deep-seated early love for watches. It wasn’t really like that for me – I just kind of stumbled across it and took a chance on it. And here I am.

It’s refreshing to hear that. Because you come across people who it seems were destined from the day they were born to become a watchmaker. But here you are, a chap who had a crack at something and found a passion in the process. Were there any early indications though? Did you have an interest in mechanics or cars?

Well, I love Formula 1. So, I guess that’s probably the closest thing I can relate to. I grew up watching that and I, I still love that. To this day. I’ve got my own racing simulator. So, in a way I kind of do my own Formula 1. But yeah, I love cars. That’s also something I want to pursue in the future. I want to restore an old Mustang, there’s a lot of things I want to do in that world as well. So that definitely interests me. I was just interested in cars though; I never really tinkered with them or took any apart to see how the engine works.

What was watchmaking school like? Oddly enough the watchmaking school curriculum isn’t well known amongst watch enthusiasts – what’s the process like and what sort of techniques do you focus on?

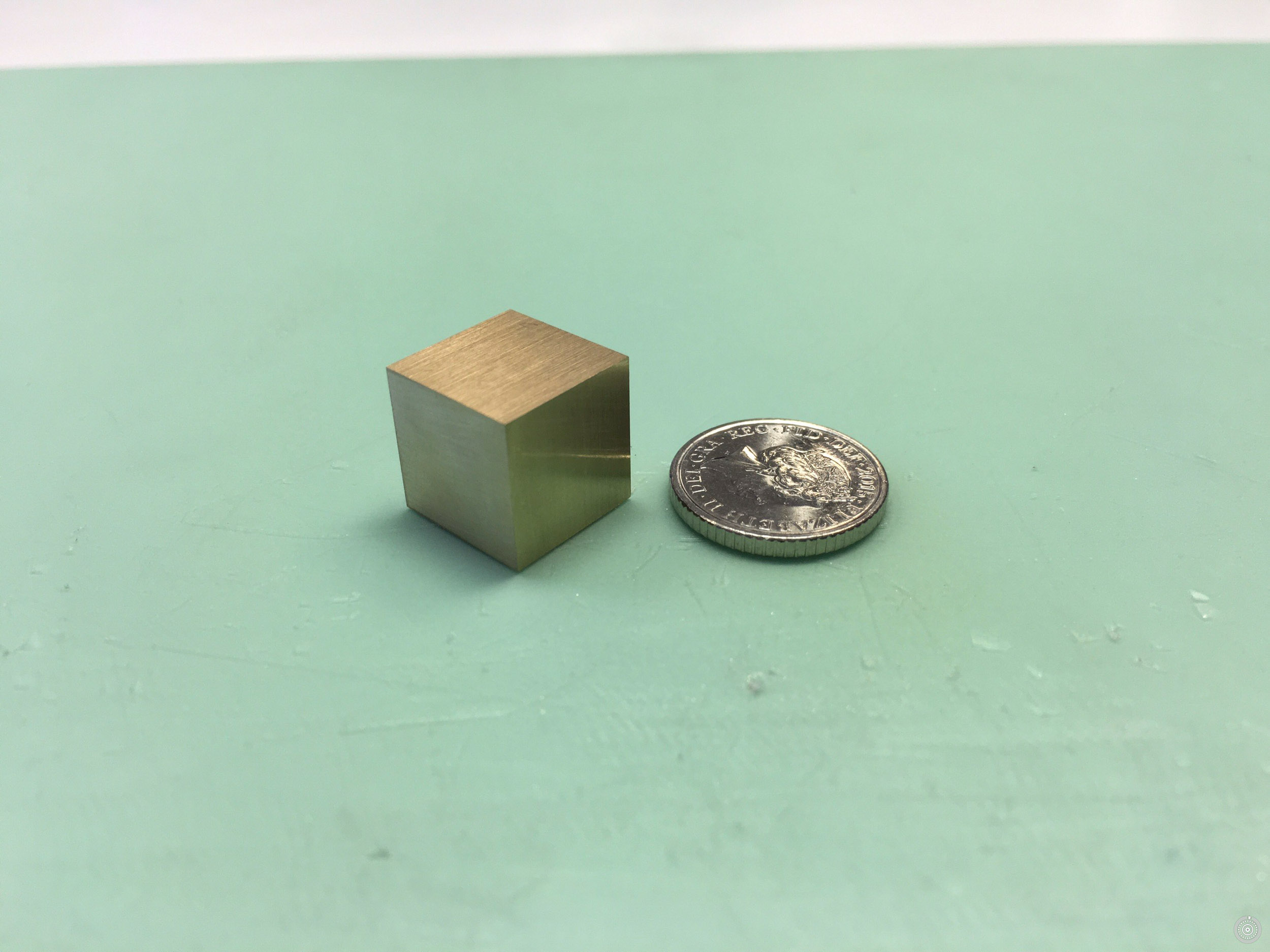

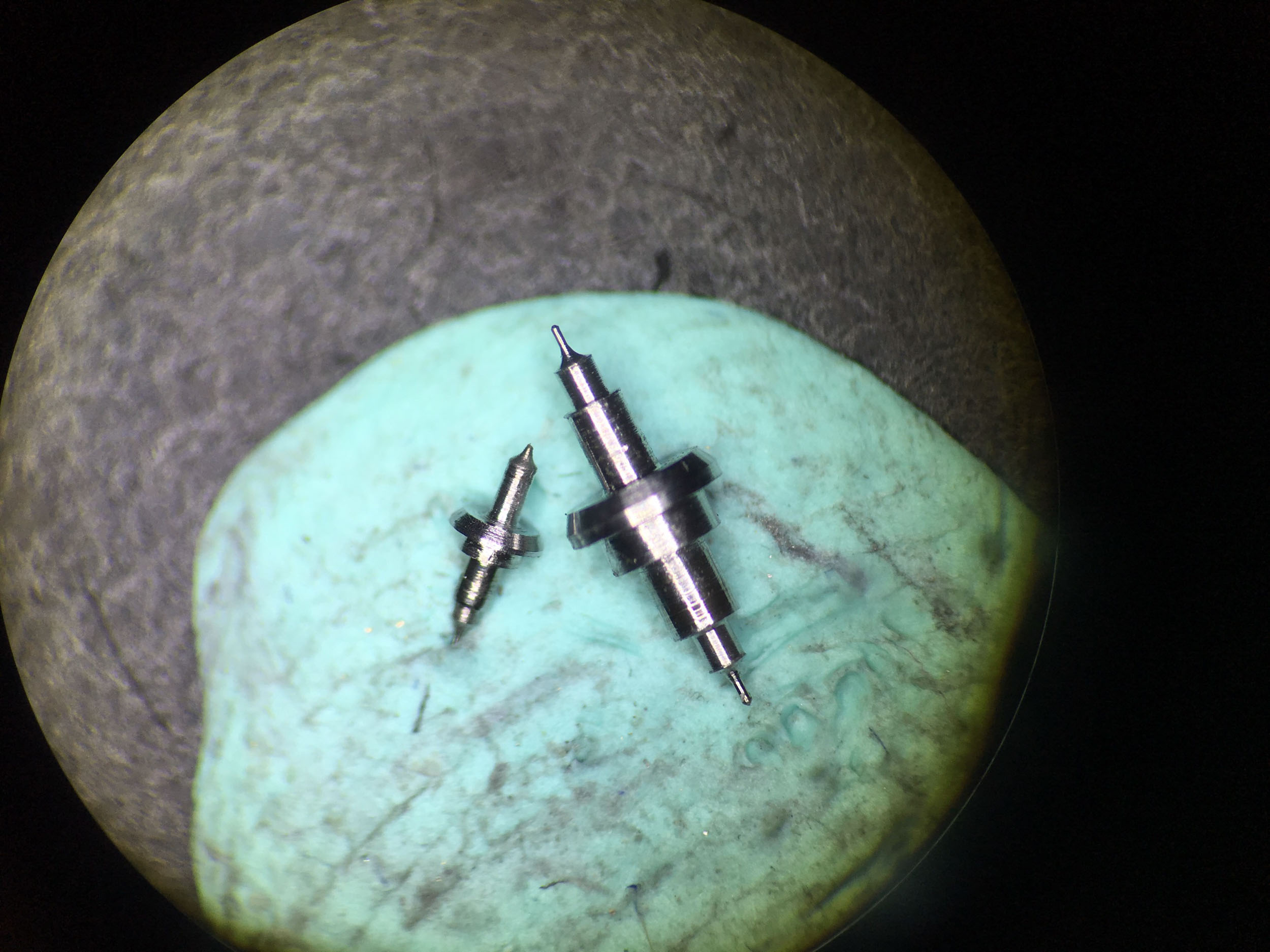

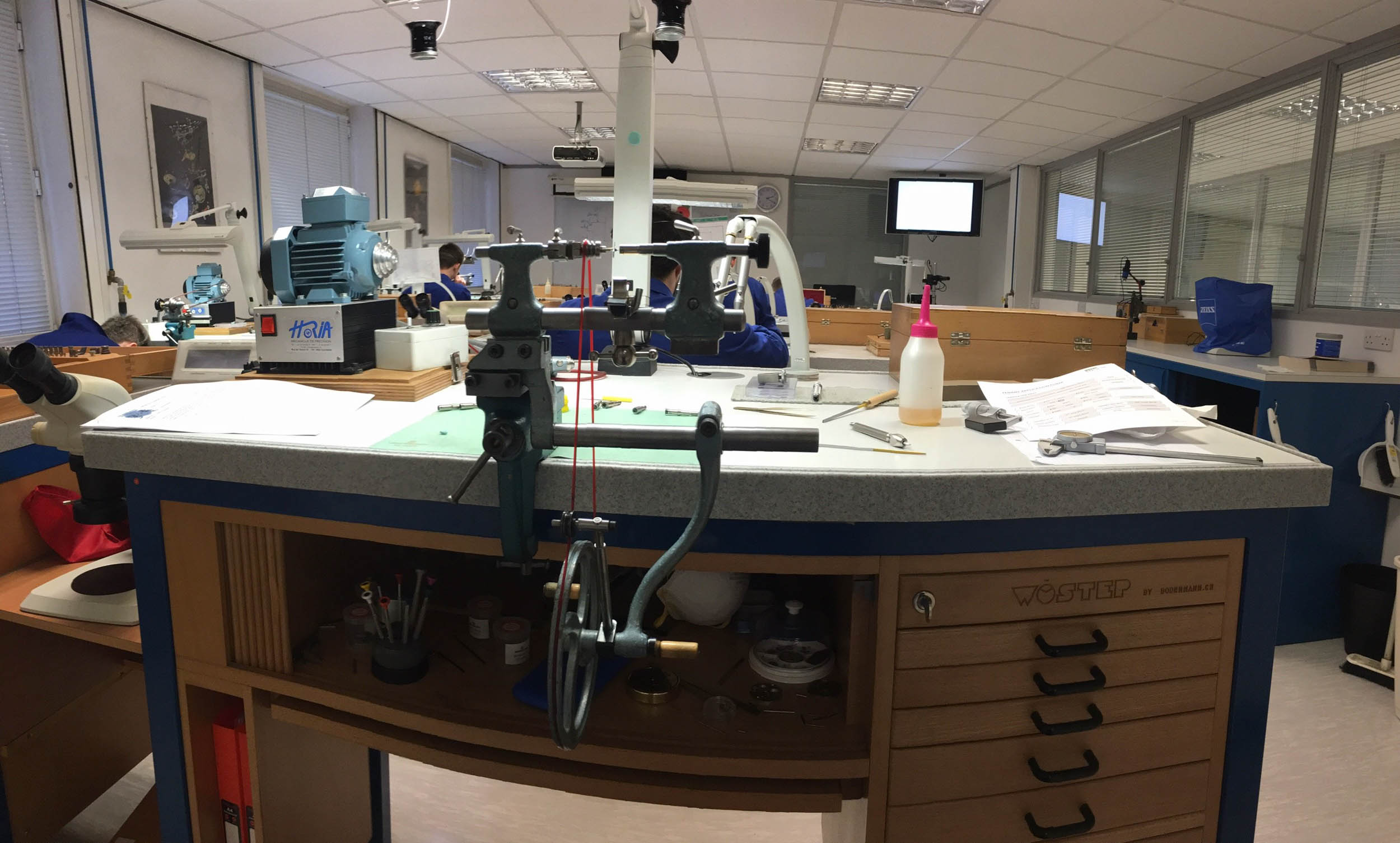

Going straight into it, the first six months were in micro mechanics at The British School of Watchmaking. So we started off just by filing, I think, I think the first thing we did was file some wood, and I don’t think there were any measurements we had to stick to, or maybe it was like, need to work with a tolerance of +/- 10 mm, which sounds a very small amount, but it’s actually a large amount when it comes to watchmaking. So, they’re just kind of easing us into it and then it was we had to file a cube of brass and to hold a couple of hundredths of mms on each side. And then it moved on to working on the lathes, the hand lathes and we’re making components like winding stems, balance staffs. Which formed the basis of the first two exams we did.

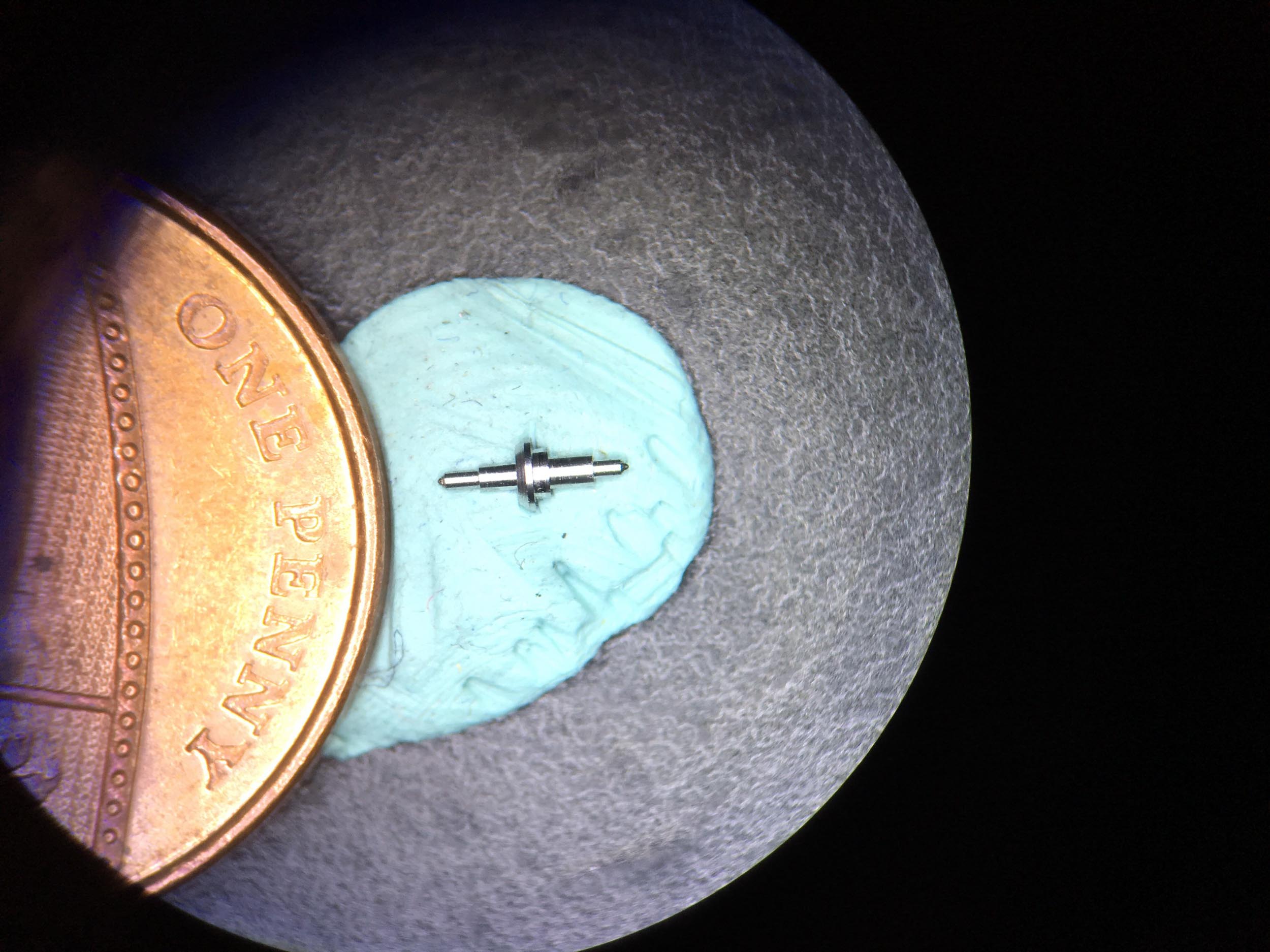

For the winding stem exam, you have to produce a winding stem from start to finish in 8 hours. You’re given a drawing you’ve never seen before and you have to make it from scratch. The next exam was the same but with a balance staff. Following on from that, the next 18 months basically focus on servicing.

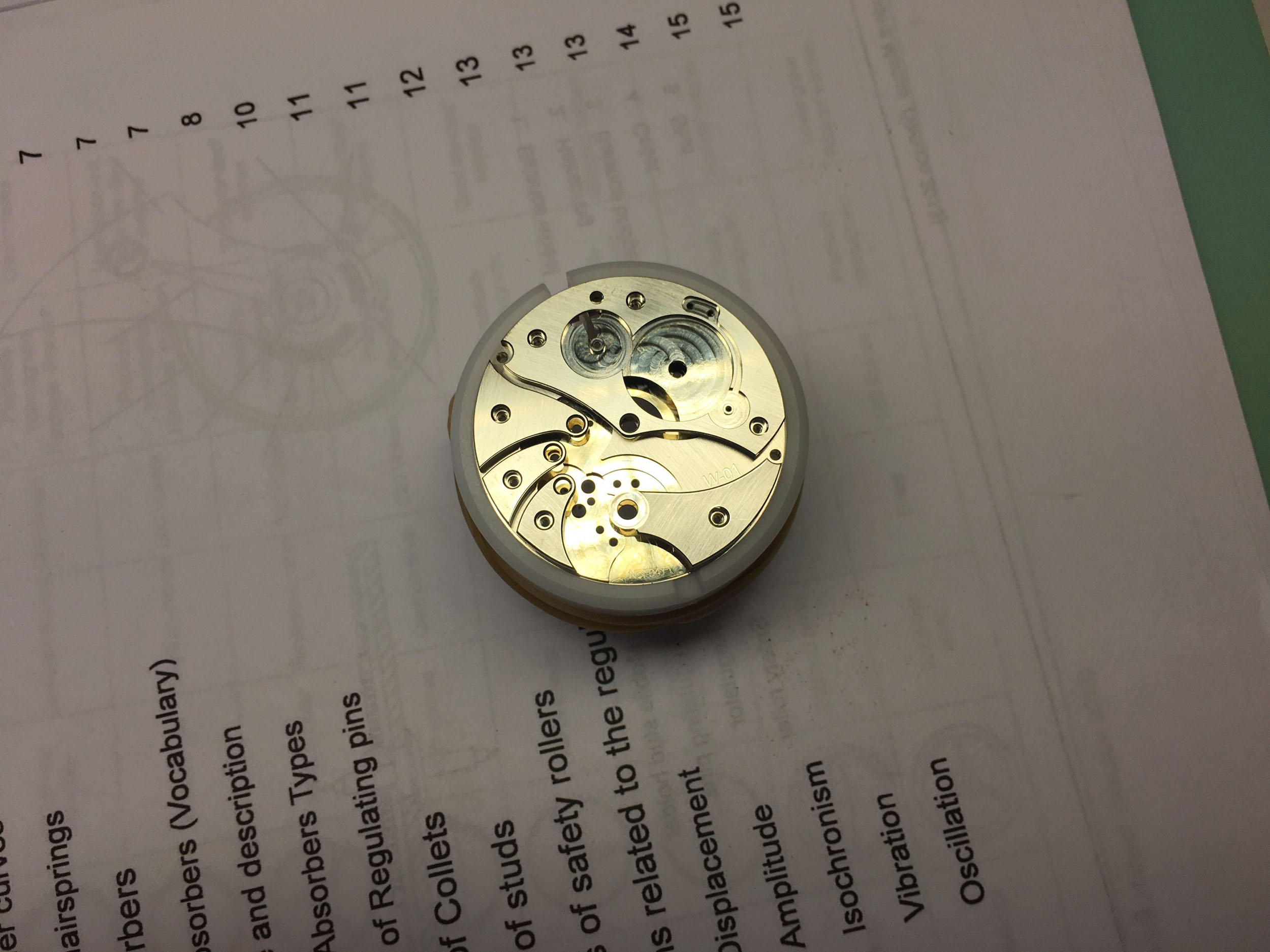

That but also thrown in what’s called the W01, which is WOSTEP’s own Calibre, and that’s part of the curriculum. You have to finish a watch using that to complete the course.

So, you’re given basically a base Calibre that’s completely unfinished. This comes in all of its raw components, and you have to finish all the bridges and polish everything. We have to make the balance stuff, the handspring, the wining stem for it, then it’s put through rigorous testing and sent off to Switzerland to get checked.

And then yeah, then it’s just a lot of servicing after that really. You get to do a project watch as well, but it’s not the main focus. You mainly just start off on a simple three-handed watch. Then you move on to some complicated stuff. And then you also get to do automatic watches, then from automatic watches to chronographs. Chronographs are kind of the peak of what you learn at school. In the final exam you’ve got to service an automatic watch, a quartz watch and a chronograph – all within two days. So yeah it all kind of comes together at the very end, whereby you put everything you know into one exam.

How’s the watch community in the UK from the perspective of a watchmaking student? It’s quite a close-knit community of watchmakers, curators and connoisseurs.

It is quite odd, because it is a very small industry in the UK. So, when I went to work at Roger Smith, someone would say a name and I’d recognize who it was, or I’d know someone who knew that person. It definitely seems like everyone knows everyone in the industry. If you go to an event, then I’m sure you can probably know someone through someone else pretty easily.

With regards to the school, the British Watchmaking School is actually funded by in part by a lot of the major brands. You know, there’s Richemont, Rolex, Swatch, Patek Philippe and they all kind of collectively pool in resource and send students themselves to the school. So, from the students are connected to the brands as well. In the – when was it? It’s in the last six months of the school, students get to do a 3,000-hour course which is what I did, and you get to go to Switzerland and visit a lot of the factories. We visited Rolex, Omega, Patek Philippe and you get to see all of this because they have close relationships with WOSTEP.

Is the experience of visiting the factories different for a watchmaker? Do you get to spend time at the bench?

You are still funnelled through some of the factories. You see all the machines and the tools, so yeah they’ve got it down to a tee, but it’s still interesting to see because at watchmaking school you’re taught to put on hands with a little stick basically, and then you go and see they’ve got this massive machine which calibrates everything, you just press a button and it goes to work. It’s interesting to see that side of watchmaking.

And what do you graduate with?

The British School of Watchmaking is a WOSTEP accredited school. I’ve got the WOSTEP certificate, that’s my kind of watchmaking degree, if you will. So, the WOSTEP School in Switzerland is like the mother ship and then there are schools all around the world that all operate under the WOSTEP syllabus.

Most jobs when you’re looking for them it will have the Swiss kind of qualification under the job requirements. So yeah it is very well in places like America, in Switzerland in here as well. So, yes, is a good qualification definitely.

After graduation, where did your classmates go on to work?

Well, so it’s kind of a given that you go to one of the big brands really. In my class there were eight students. From that, six were sponsored by a company and then there’s two that were independent. So, I was one of those, I wasn’t tied to a company.

In my class, there were three Swatch watchmakers, one Richemont, and then one Breitling. So, they were all contractually obligated to go to those companies after graduating. But yeah, most of their thinking was to go into that kind of work anyway, I think it’s quite rare for someone to leave and go into the making side of things, which is where I was very lucky; the fact that a job came up at Roger Smith’s workshop. It came up about two months before I did my final exam, so it all lined up perfectly. So, the second I graduated, I was able to go to the Isle of Man right away.

How was the move over there?

It was easier than I thought, I thought it was going to be the hardest thing for me. But, coming from watchmaking school in Manchester, it was actually an easier transition going to the Isle of Man than it was the initial move up to watchmaking school from Somerset. By the time I had to move to the Isle of Man, I’d already been away from home for two years. But moving to the Isle of Man was actually slightly more convenient than being in Manchester because Manchester was about a four-hour drive to anyone I knew. So, it was much quicker actually. But, yeah, the Isle of Man is a lovely place – wasn’t exactly a chore to move over there.

After working with Roger Smith you came back to London, I presume?

Yeah so obviously Coronavirus has thrown a spanner in the works, because after I left Roger’s I had planned to come back to live with my parents just for a couple of weeks before I moved to London. But then because of Coronavirus, that’s all been put on pause. The plan, once all of this is over is to find work to start seriously pursuing becoming an independent watchmaker.

How do you go about preparing to become an independent watchmaker?

Lockdown has really allowed me to dive into honing my CAD skills, and I’ve even gone so far now as to model my first wristwatch calibre as well. So all the complex maths work is done for two different watches now, the hardest bit is equipment actually.

I’ve made a list of everything I need to be able to produce my own watch from start to finish. Just to set up a workbench and get all the tools needed, it would come to around £7,000. Add on a Schaublin lathe and that’ll add another £30,000 and another jig for around £20,000. It adds up quickly. I think the biggest challenge is acquisition of those tools. One of the hardest things about leaving Roger’s was that I had access to all of those tools. So that was never an issue there. I’ve got my own small lathe and I’ve got my own little CNC machine as well. So, for the time being, I’m able to prototype things and make a few bits and bobs at home in acrylic. I’m able to make certain things, but I’m just going to be saving and acquiring equipment when it comes available.

Would you get a mix of new and old machinery?

In his book, George Daniels says that buying second-hand high precision machinery is a bit of a gamble. Because it has to be high precision, if you’re buying second-hand you don’t necessarily know the history of it. The plan would be to get brand new everything. But, obviously, if I can’t do that, I can’t do that. For certain things I’ll have to find a way around it, because for things like engine turning, they don’t make straight line engine turning machines these days. You either have to make one yourself or find a really old one, which will be very expensive.

What’s your aesthetic style and what sort of complications do you want to pursue?

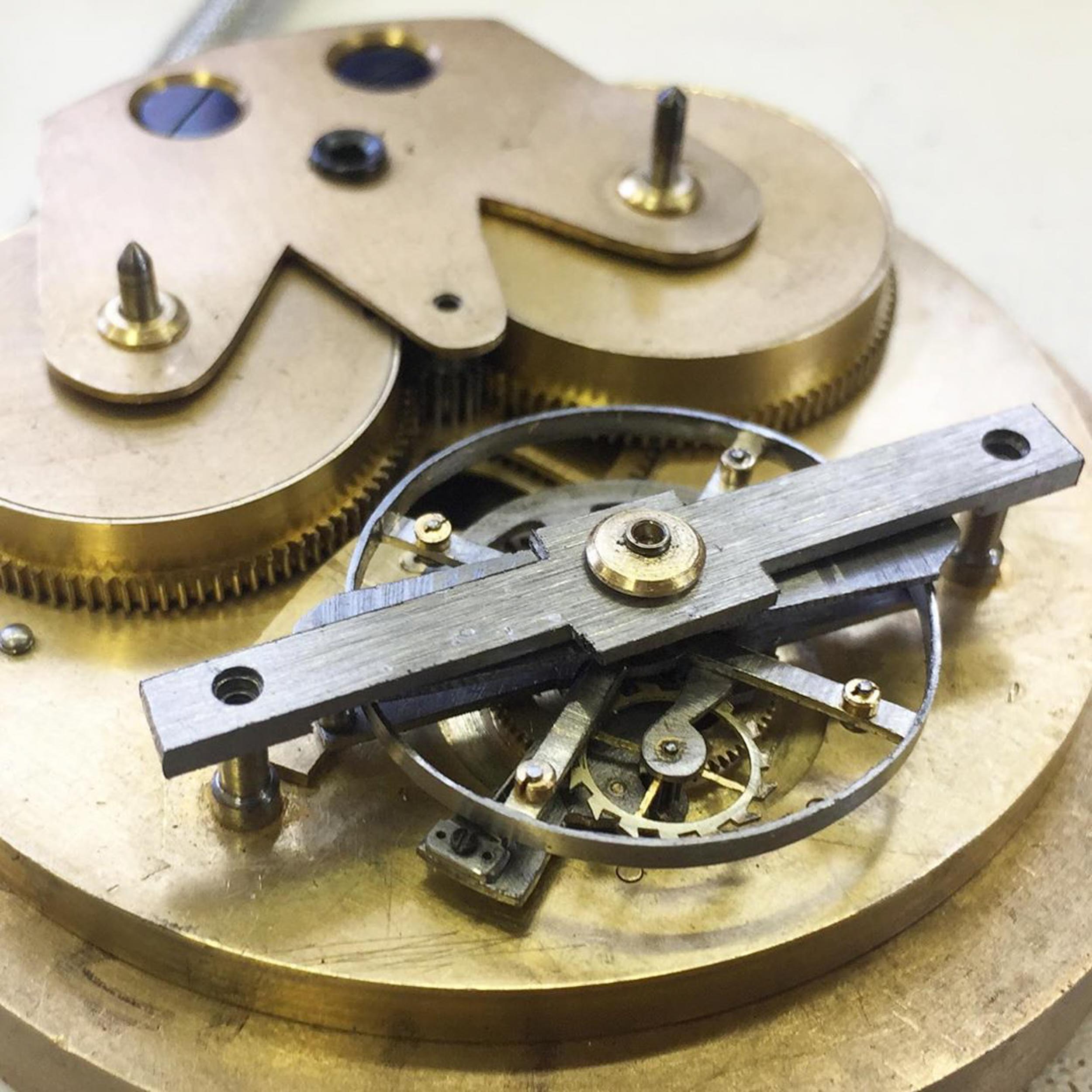

Yesterday I finished doing the 3D model of my spring detent tourbillon pocket watch. It will look really cool is a mix between the aesthetic styles of George and Roger. In the future, I’d like to breach into a space that hasn’t been done like what George did. He kind of initially worked within the style of Breguet. But, when you look at George Daniels watch, you can tell it’s a George Daniels. I’d like people to look at my watches and think that way, but also see the influence my inspirations have had on me. They’re definitely going to be classic in style, and there’s going to be the same kind of finishing styles that Roger Smith does. Because that’s what I’ve been trained in, and now I’m very good at black polishing and sandblasting and things like that.

So, I’ll keep it traditional in that sense. In terms of complications, the things that really interest me are kind of the higher up complications. So, tourbillons, chronographs, perpetual calendars, minute repeaters, they’re all the things that in the future I want to be making wristwatch versions of. I want to be building those mechanisms in a new way. A way people have never seen before. Much like what Rexhep has been doing with AkriviA. They have crazy looking watches, but at the same time, they look classic.

You look at guys like Dufour who’s known for his finishing, but then on the other hand Daniels didn’t chase the nth degree in terms of finishing, he was more concerned with invention. And then you’ve got guys like Rexhep…

…who have managed to bring together both the two different schools of thought into one watch. Yes, exactly! That’s the direction I think is needed if someone is to stand out and I obviously want to stand out. I think that’s where you have to kind of go because there are people being very inventive at making these new mechanisms, but they don’t look very good. But then on the other hand you come across simpler watches that look amazing. If you can do both, which is my aim, that’s amazing.

Branding isn’t necessary at that point…

When you hear “Perpetual Calendar Tourbillon” that’s going to perk your ears up anyway. And if you hear it’s been handmade by one person, that’s also going to get you even more interested. So yeah, I don’t think you need this massive allure behind you. Just hearing that alone will attract people, though if you can’t back it up with a decent watch you will never succeed.

Who are your inspirations? Horological heroes if you will.

Really old watches don’t particularly interest me because it’s very early in the development of complications and have styles I don’t particularly like. I’d say George Daniels is definitely my idol. Roger as well, even though I’ve worked for him – I’d say he’s one of my idols in watchmaking. If I could achieve just a fraction of what he has then I could safely say that I had an incredible career. Philippe Dufour, he’s just got this kind of weird aura around him where you say his name, and everyone just instantly knows him as one of the best watchmakers ever. And then in a way there’s another set of idols, the young guys currently leading the way. I’m talking about guys like Theo Auffret and Remy Cools.

So yeah, there’s a few guys that are doing really cool new stuff and they’re kind of what’s motivating me to get going with everything. Because if I can get the traction that they’re getting, but also do it in England – bring everything back to London – that’s a win-win!

The next generation definitely seems more collaborative and open to throwing around ideas amongst themselves – it’s nice to see.

Yeah, I think the industry is definitely coming out of the way it has been in the past. It just seemed to be very tense in the past, everyone was tight-lipped and just kind of looking over their shoulder, making sure no one’s looking at what they’re making. I definitely want to go down that road and be as transparent as possible. I think too many people are too afraid that maybe someone will copy you – I think there’s much more respect these days. It’s defiantly a more open, supportive environment than what it was like in the past.

I’d like to do my own YouTube channel, a bit similar to how Reuben is doing it. But, instead of adding commentary I’d just like really nice macro cinematography with some quiet audio in the background. No speaking just detailed visual demonstrations of techniques that you normally don’t see. The BBC did a similar series for furniture and other objects, they’d just show the process and highlight the artisanal aspect of it. That’s what gave me the idea. The viewer would be more interested in it because you have to focus harder and not get swept up by the audio.

Thanks James. It’s been a pleasure.