Collector’s Guides • 04 Aug 2018

Hands on the World – Patek Philippe World Timers

Where the august Genevan maison Patek Philippe persists in remaining distinguished, well-elevated from its peers, outstanding – yes, even considering that young Saxony upstart – is indubitably in the domains of the complications or high complications. Of those, a great few with the possible exception of the annual calendar, were conceived multiple decades if not centuries ago with the intent to meet existential and professional demands, through war [1] and peace [2]: the perpetual calendar chronograph, the monopoussoir chronograph, the rattrapante, the minute repeater, and perhaps the most iconic: the worldtime watch.

It will not be news to most that Patek Philippe has in 2017, collectively united and brought to market two of its most illustrious complications in the marvel known as the 5531R – a watch unapologetically classical in appearance, belying a singular accomplishment achieved by none before – a minute repeater which chimes the local time wherever you are on the globe, predicated on whichever of the 24 cities is set at the 12 o’clock reference index. Behind its gorgeous cloisonné enamel dial, a technique never before applied on a repeater by Patek, and one of its specialties – depicting the Manhattan skyline if you acquired one of the ten made for the New York Grand Exhibition – or of the Lavaux vineyards on the shores of Lake Geneva in the ‘regular’ production pieces, this unique mechanical functionality is made possible by the hour snail cam of the repeater mechanism being continuously driven by the time-zone wheel of the worldtime mechanism, unlike in conventional repeaters where the hour snail is indexed hourly by the minute snail. Other novel techniques employed in the 5531R include a fail-safe time-zone pusher, disabled while the repeater is activated – and the mounting of the repeater gongs on the caseband rather than the baseplate.

The lineage of Patek Philippe worldtime watches may be traced to the rectangular-cased Ref. 515HU for “heure universalle” – world time, conceived by a Monsieur Louis Cottier [3] at the behest of Patek Philippe in 1937. Cottier was born in 1894 to Emmanuel Cottier, an accomplished maker of watches and automata in Carouge, Geneva. Cottier senior had in 1885 presented a World Time conception to the Société des Arts, which though unsuccessful, served as inspiration for the complication which his son executed to great renown in 1931. Emergent during the last vestiges of the Industrial Revolution and accompanying the expansion of railway networks, the worldtime complication pre-dates the jet age of the fifties: during which tool-watches such as the Rolex GMT-Master, commissioned by Pan Am, were widely adopted. And unlike GMT watches, which serve only one or two additional time zones, with a true worldtime one is able to directly read the day/night time in the other featured (usually twenty-three) cities by virtue of a demarcated light/dark inner chapter ring that revolves once in 24 hours.

Cottier’s patented solution was to feature the local time, displayed by centrally-mounted hour and minute hands, mechanically coupled to an inner AM/PM rotating ring, read with respect to an external bezel on which the names of the twenty-four cities are inscribed. In 1954 the Ref. 2523HU was introduced: the first Patek World Time watch with two crowns, credit going to Cottier, the second of which enabled the city disk to be adjusted and integrated as an extension of the dial, under the crystal. The inherent robustness of this solution enabled the city names to be printed, rather than etched, which improved legibility. All Patek Philippe worldtime watches henceforth have an integrated city-disk, and from the Ref. 5110 of the new millenium, manipulated by a pusher at 10 o’clock.

What makes a watch desirable, so that it is exhilarating to behold and to cradle in the first encounter, yet robust, accurate, pleasant to wear on a daily basis over decades?

I hold that a good watch is largely a function of superb mechanical prowess, which is, in my mind, the overarching criterion on which consideration of ownership is predicated – a movement which is coarse or pedestrian in design, tactility, or dimension is immediately off-putting to this somewhat pedantic rocket-scientist. Next would be the dial: the medium on which what we know as linear time is displayed, and the largest by visual surface area. An interesting dial, first of all, displays time well; at the quickest glance it ought to provide the owner with all the information relevant to the complication. The best dials, however, do that and more: have you noticed the lateen-rigged craft just off the Lake Geneva shores on the cloisonné of the 5531R?

But there are more emotive elements to a watch with magnetic charm than a well-executed dial and movement: haute horlogerie, after all, transcends the demand to merely have objective time (assuming an inertial frame of reference) on hand. A watch which one straps on and knows is perfect has an air of order and balance about it: from the way the lugs curve to meet the wrist, the mass distribution of the case relative to its height, the contours of the bezel as it joins the middle case, to the suppleness of its strap or bracelet. The best of them are historically unassailable: there is no discontinuity in execution or functionality from the historical purpose for which the watch was created and is marketed. The ethos of the brand is palpable – wearing such a watch is an acknowledgement of a mutual sympathy between wearer and creator.

What makes collecting Patek Philippe watches so rewarding? My view is that any entity worth studying in detail must possess the quality where differing degrees of complexity are apparent at different levels of resolution: perhaps that is the intrigue of great automobiles and aircraft, a handmade suit, a gripping artistic or literary work – Monet or Dostoevsky for instance – unlike in chaos theory and the evolutionary tree, where a fractal manifests as self-similar geometrically at differing degrees of scale, a magnificent objet d’interest generates a landscape of interest, with the nature of the object varying in the collector’s perception as it is examined and critiqued by the metrics with which the functional, aesthetic, and tactile utility of the work is analysed.

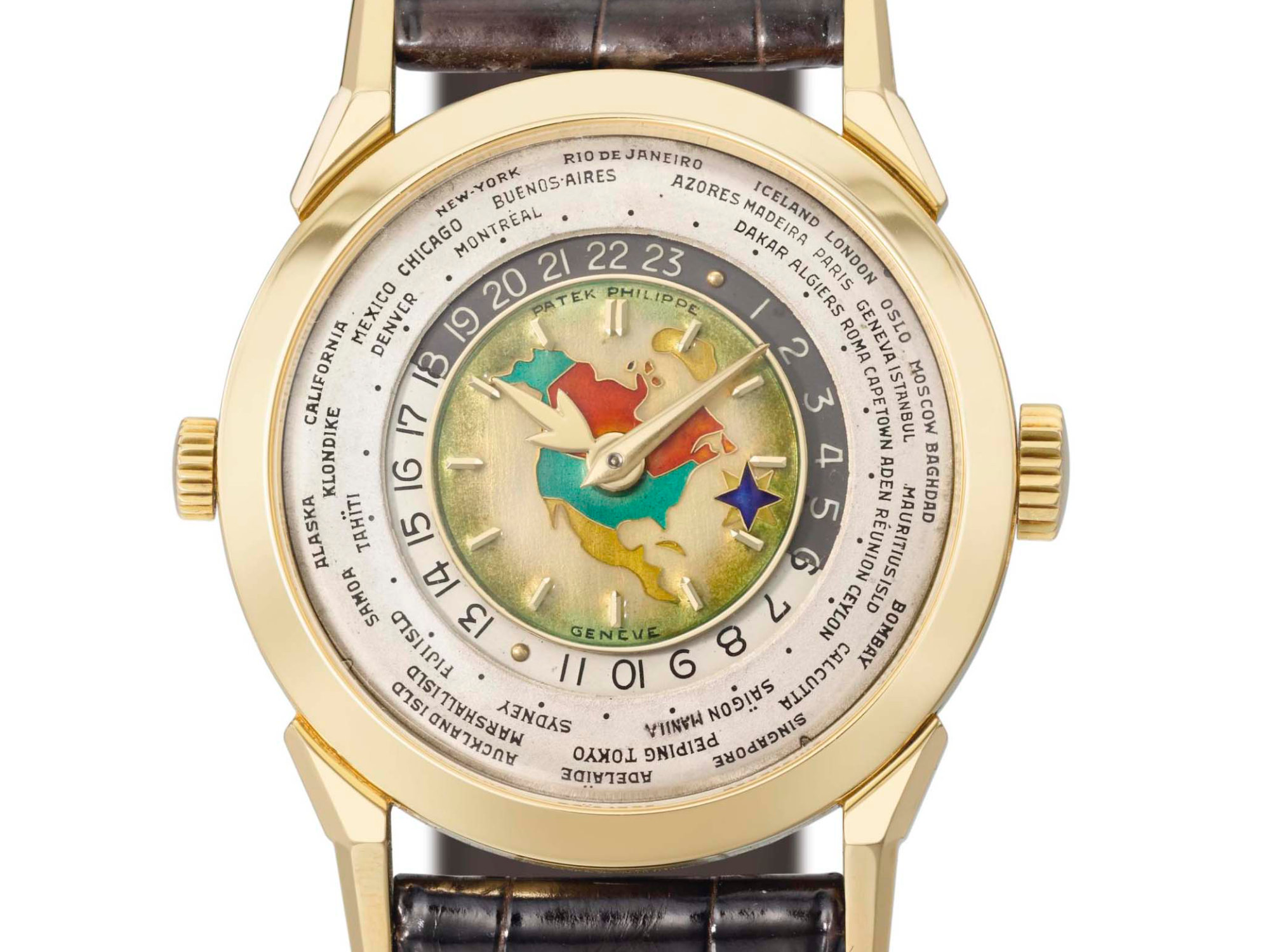

The Ref. 5131J of 2008, shown below, is such an exemplar: it is simply gorgeous, on and off the wrist. The yellow gold “J” is the first modern execution of a Patek Philippe Worldtime with enamel medallion, and while many argue that the quality of the cloisonné enamel is superior in the later white gold ‘G’, rose gold ‘R’, and platinum ‘P’ versions, the writer is partial to it for its warm hues. In the later three executions, the fringes of the continents cast a lighter halo into the blue of the sea, a gentle visual delineation from the shallow coastal waters and not seen on the ‘J’ nor in the early enamel worldtime watches. The still-recent 5131R is no longer featured on Patek’s website, and given the marque’s reticence on model continuity, one wonders if the latest and arguably best-executed 5131P, possibly the final Patek worldtime offered in cloisonné enamel, is also on its last legs.

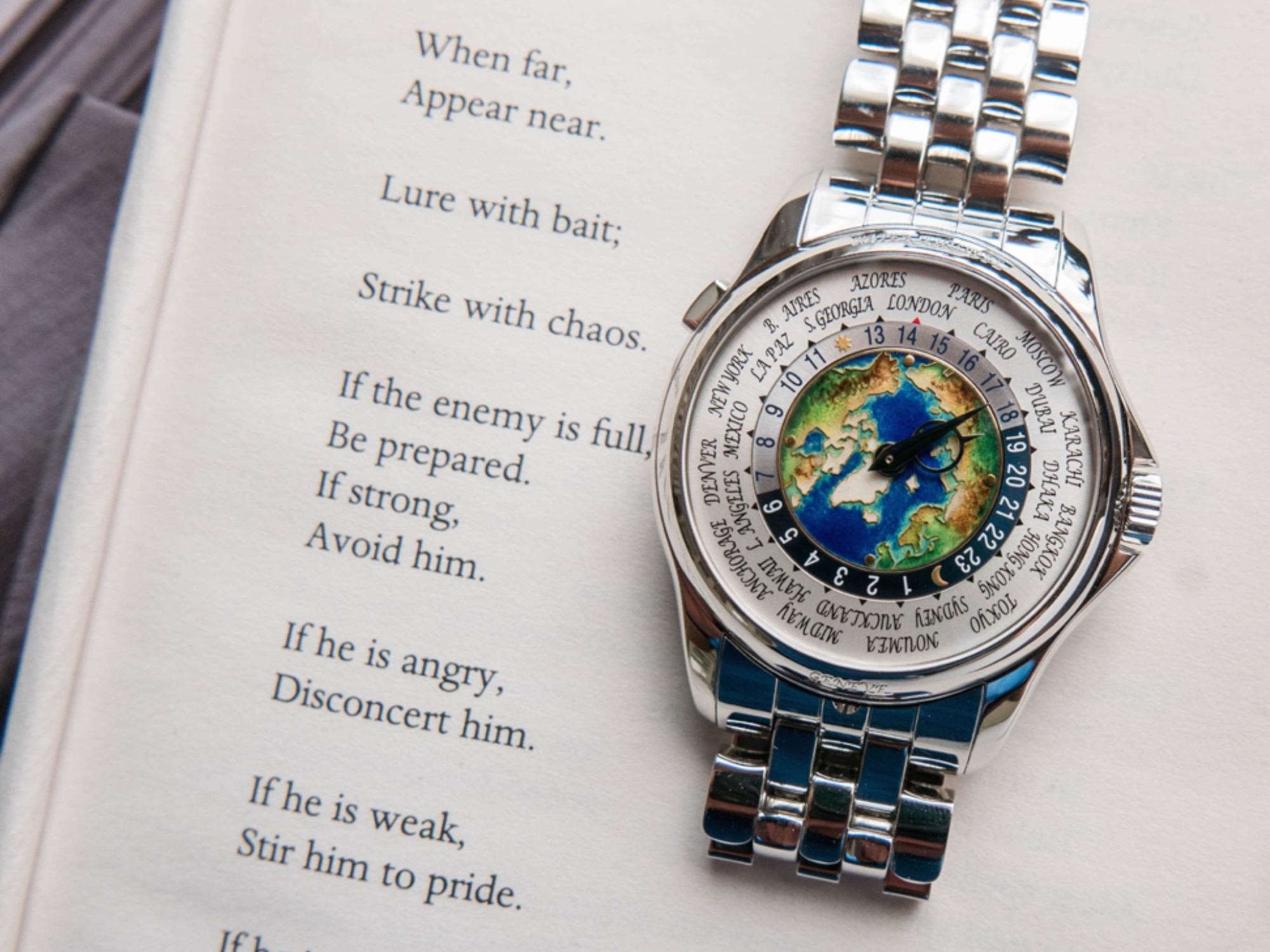

Of the regular, recent world timer watches, the 5130P, now discontinued, is my undoubted favourite: the ice-blue guilloché sunburst dial in heavy relief coupled with the aiguilles ciseaux ‘scissor’ hour hand and reassuring heft makes its own case (unintentional pun). The current iterations of the standard worldtime, the 5230 in white or rose gold, are equally compelling: with the superbly balanced 38,5mm case and modern slate-grey centre medallion – guillochéd by hand on a rose engine – it is clearly of its time, yet evocative of the mystery of global exploration associated with the mid-century advent of the jet age. Its hour hand is reminiscent of the Southern Cross constellation. Ad astra, orbis non sufficit.

Should one desire an even more dynamic package in what must be the ultimate traveller’s timepiece, look no further than the 5930G – which combines a worldtime complication with a self-winding flyback chronograph in a very contemporary, stunningly blue iteration of the only other chronograph-worldtime that Patek has made, the specially-commissioned Ref 1415HU of the year 1940.

Women who find the 38.5 or 39.5 mm cases of the Refs. 5230, 5131, and 5930 too obtrusive may turn their attention to the captivating Ref. 7130 in rose or white gold: the latter in peacock-blue, and gorgeous on a lady.

What does the future hold for the lineage of Patek Philippe’s most iconic complication? A natural evolution would see the 5230 offered in yellow gold and platinum. As to the rare, enamel pieces, it remains to be seen if Patek will explore other enameling techniques after the eventual discontinuation of the 5131P: champlevé or miniature-painting, possibly – the former presents an inherent difficulty, given that it is a ‘reductive’ process, where metal is carved away and the resultant cells filled with enamel – rather tricky to execute on a small medallion. Then there is the question of diplomacy as well; given the marque’s commitment to the Chinese market and the likelihood of future Grand Exhibitions in the region, it is not inconceivable that the nomenclature for the present GMT+8 time-zone may be replaced with that of Shanghai in future incarnations. Is it possible that Patek will offer the potential of limited, modular exchange of its worldtime city-disks in future references – or more, an entirely new reference with the accompanying gear modifications, to incorporate the half-longitudinal (or even more idiosyncratic three-quarter-) time zones: those of India and Iran, for instance?

All that is a speculative exercise. What avails to anticipate is the 2019 Patek Philippe Grand Exhibition in Singapore, confirmed [4] by Mr. Thierry Stern, slated to take place mid-year – and if the 2017 New York template is anything to go by, the showcase will be exhaustive, the limited editions exquisite, and yes, the city-state’s infrastructure, faultless.