Interviews • 13 Oct 2020

Max Büsser on Leaving His Comfort Zone

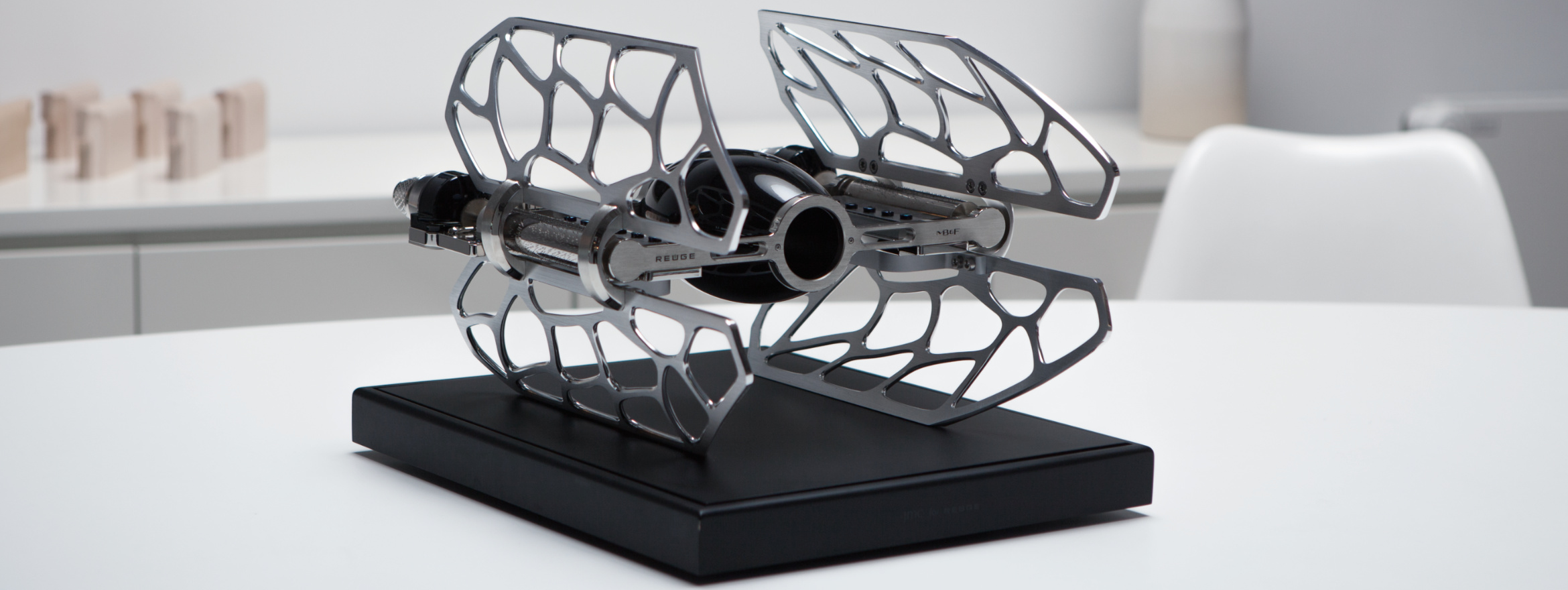

Nowadays, he’s best known as the founder and owner of MB&F. But it was his previous role as CEO of Harry Winston Rare Timepieces where Maxmilian Büsser started making his mark in the recent history of independent watchmaking. The Harry Winston Opus series – an annual, limited edition of haute horological pieces – was an unusually transparent collaboration and brought wider attention to independent watchmakers such as Vianney Halter, Felix Baumgartner (of Urwerk), Christopher Claret, Antonio Preziuso, and Francois-Paul Journe. This spirit of showcasing talent has continued in recent years in the form of the M.A.D Gallery, where MB&F creations and curated pieces of mechanical art complement each other.

There’s no better person to tell Max Büsser’s incredible story than the man himself.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

I didn’t believe I was an entrepreneur

There was absolutely nothing in my background to become an entrepreneur. My dad used to work for a big corporation; everybody around me aspired to work in a big corporation. I think Jaeger gave me a taste of what entrepreneurial spirit was, because when I started working there in 1991, it was so much smaller, and battling to try and survive.

I sort of love that. It’s weird, because when I look back, I don’t think I thought it was that great back then. But now, I’ve got this romantic image of what my beginnings at Jaeger were. It was an incredibly strong culture of watchmaking. We would come up with minimum one calibre a year. We were pioneers in watchmaking in those days.

When I arrived at Harry Winston, there were seven employees in the watch division. And only one of them were in production. Everybody was virtually clueless on watchmaking. The company itself had a culture of being a high-end jeweller and a retailer, and watches just weren’t part of that expertise. A lot of the watch production was subcontracted out. The watch division was virtually bankrupt. And New York basically tells me, “either you save the company, or we bankrupt it.”

Harry Winston was a de facto entrepreneurial adventure, even though I was in a company, because the only support I had was from Mr Winston himself. Nobody understood what we were doing; yet, because we were growing so fast, everybody at Harry Winston just let us do whatever we wanted.

It was very much thanks to these adventures that I got the courage to create MB&F, because I sort of understand that I’ll be okay. I don’t enjoy being in trouble, but I hate being in my comfort zone.

I would not have wanted to be my boss

The Opus watches happened because most likely I never asked the executives at Harry Winston if I could do them. I was always extremely polite and respectful, and I would always inform Mr Ronald Winston. I was very lucky because, even though he didn’t understand the watch industry, he trusted me for a reason I still don’t know. I would make my case to Mr Winston, and he would go “okay”. I don’t know if it’s just because he didn’t want more issues to deal with, or because he liked and trusted me. On the other hand, he wanted to sign off on anything coming out, which is perfectly understandable. For Opus One, it was pretty easy because it was a Harry Winston case with a Francois-Paul Journe movement. But where it got really tricky is when I decided to do Opus Three.

Vianney Halter came to me with this design, and I think it’s fantastic, let’s do this. Back in those days it was only a 2D design. And I’m thinking, how do I convince Mr Winston? So I wrote to Mr Winston, when is the next time you’re in Geneva? “Oh I haven’t planned to be in Geneva for a while.”

I didn’t want to jump on a plane and show Mr Winston the design; I wanted him to come with me to see Vianney. Because I thought if he goes to Vianney’s workshops, if he meets Vianney, if he understands how this whole crazy scientist approach Vianney’ has to the world, then maybe he’ll validate this product.

Mr Winston had flown from the US to Japan and decided to fly back from Japan through Europe and just did a stop in Geneva, for me. I go to get him at the hotel in the morning, he was completely jet lagged; he hadn’t slept. Mr Ron Winston was an incredibly polite, respectful, nice gentlemen. He arrived, and sat in the car like a grumpy old bear. “Remind me why we have to do this and why the hell am I here?”

This is not starting the way it should be starting. We drive the hour and a half up to Sainte-Croix, I start painting stuff to him, his mood hadn’t changed. We got to there, Vianney and I took him through the workshop where everything is done by hand, and show him some pieces, including the Antiqua. Vianney then left the room for whatever reason. Mr Winston said, “oh he’s a wonderful gentleman, isn’t he? Thank you very much for bringing me to this workshop, it’s very enlightening, but I really don’t like his watches.”

Two minutes later Vianney came back, and we unveiled the design to Mr Winston. We start talking about all the features. I make Vianney talk about the design, the movement… Mr Winston doesn’t say anything. We’ve stopped talking. Mr Winston is looking at the drawing. You know what minutes can feel like when you’ve put years into a project and this guy is going to say yes or no.

Suddenly Mr Winston lifts his head. “This is remarkable.”

It gives me goosebumps, just thinking about that moment. Vianney and I were keeping our composure as much as we can, but inside we’re like two little kids, going “yes, yes, YES!!!!”

When Vianney left the room again, Mr Winston looked at me and says, “do you think I can have one of his Antiqua watches?”

From then on, Mr Winston gave me complete free rein. It took ten years for that watch to be delivered, and by then I had left Harry Winston. The Opus 3 has sold for some incredible prices recently; clearly, 17 years later, finally people are understanding that these are seminal pieces. I’m not saying that because I participated in it. They are seminal pieces in the history of watchmaking, because they redefined the genre. Because they took insane creative risk, on top of of crazy engineering. And there are very few of those pieces in the history of watchmaking today.

It’s about the journey

A young man ambled into the Harry Winston booth at the 2003 Basel Fair. We had just unveiled the Opus 3. He has a steel prototype of this watch, and asks to see me. His name is Thomas Baumgartner; his brother is Felix Baumgartner, and this was the very early days of Urwerk. I remember calling my whole Harry Winston team over to come and look at this watch, which would eventually become UR-103. Of course with the crazy schedules of Basel there wasn’t enough time, and since their workshop in Geneva was only 800 meters from ours, I met with them after the fair. We talked, and I said, “Guys, we have to do an Opus together.”

A year or so later, Felix called and asked to see me. He arrives and shows me two of his ideas. One is the piece that you know as Opus V. I chose it because it was so three-dimensional and I just loved it.

Felix hurtled along, he worked day and night for a year, and made it work. That was just the beginning. It was interesting because many years later, we’re sitting on a terrace with Felix – we had become very good friends by then. This was around 2010, we were just tapering off the big crisis. We thought we should do something together to celebrate what we did at Opus V, and that was C3H5N3O9. The idea was, let’s do something which has absolutely no commercial point, we’re not going to talk about it in the press, we’re not going to do any PR around it, and we’re going to try and sell it online for 110,000 Swiss Francs. It was an insane risk, and it did blow up in our faces.

Felix and I have very different characters. We have very different ways of seeing the world, but we’ve always stayed close. I think there’s one thing we have in common – we’ve got 100% respect for what the other one has done and achieved, coming from virtually nothing.

I can actually listen to people from time to time

When I started MB&F, I wouldn’t listen to anybody. I wouldn’t ask anybody about anything, because it was about me defining myself. That person who adapted themselves to what they think other people wanted them to be, I was that young man at some point in my life. And so, as a creator, I was creating myself. My products were just a progression of that. But as I grew more comfortable with creating, and understanding what’s important to me, I grew to be more successful. These days, interestingly enough, I’m actually much more open to other people’s views.

Opus was incredibly different to MB&F. Opus was me going to a watchmaker and asking them, “do you have something cool?” And the guy would rummage in his drawers and say, “Oh, I got this”. We were patrons: the guys had free rein, we just put the Harry Winston signature lugs on. The MB&F process is quite the opposite. Of the 18 calibres, 17 are my ideas, and I find the right people to transform the concept into reality. The exception being the Legacy Machine Perpetual, created by Stephen McDonnell.

So much of the watch world is about relationship building. I think a lot of people just remember the calibres, the movements, the designs; and they forget the human relationships which ultimately built those tangible products.

In 2008, I met up with Wei Koh in a cafe in Singapore, and I had some drawings and a 3D print of the HM3. I show him the thing; it was supposed to just be the Star Cruiser (it didn’t have that name at the time, it was just the HM3 at that point), Wei is putting it on his wrist. I didn’t have a strap on under the 3D print, I just got the case. Instead of putting it like [the direction of the Star Cruiser], he keeps wearing it vertically during the discussion. And he goes, “dude, this one needs to be cool with the columns this way.”

So I came back from that Singapore trip and tell Serge Kriknoff, who had just come on board as my technical director, “I had coffee with Wei and he puts the watch the other way around. Is there a way we can have two ways of having the HM3?” I didn’t want to kill my initial idea. And so we worked on it, re-engineering the back plate and of course, the columns have to be put in differently, but for the rest it was pretty much not that complicated.

This is exactly how I function. People give me feedback, and from time to time, there are some good ideas. And I want to credit the people who’ve done it.

If you’re not shocked, you’ve got a problem

I was sitting next to this young guy in my first year of university, and asked him what watch he was wearing. I was a looking to buy a watch because my parents wanted to give me one. He said it was a Rolex – I had no idea what a Rolex was at the time, so I asked him the price. He said 4,700 francs. I gave that guy hell, because 4,700 francs was probably what I would make working in a cinema three nights a week, selling hi-fi’s on Saturdays, and giving math tuition during lunch breaks for a year. I didn’t understand how something could cost that price.

Of course I understand that most people should be shocked that a piece of watchmaking costs $100,000. If you’re not shocked, you’ve got a problem. Because the only thing I will accept is that you’re actually very knowledgeable. That you understand the whole process of how it came to be – the insane engineering, the insane manufacturing, hand finishing, the years of hard work that has gone into producing that watch, then it makes sense.

It happens to me. I remember 10 years ago, I saw this drawing of a lamp by a gentleman called Frank

Buckwald on the internet. And I thought it was really cool. So I emailed him; “I love your lamp, I’d like to buy one, what’s the price?”

I thought he was kidding when he told me the price was several thousand euro. It’s interesting because I find $100,000 for a watch completely okay, but several thousand for a lamp is totally not okay. He very kindly explained to me that everything is done by hand, and that he only makes 4 or 5 lamps a year. I decided to take an EasyJet from Geneva to Berlin to check that was right, and ended up spending an afternoon with one of the most delightful creators I’ve ever met. Someone who has dedicated his life to his art, who is living on selling three to four lamps a year. That was his revenue, not his income, because he has his own workshop and he does everything himself. And he was apologising because it was so expensive. Of course it’s not expensive – it should be more expensive. He looked at me, “at this price I already can’t sell any.”

So I asked him how many he could make in a year. “Probably ten or twelve, one a month.”

“Okay, I’ll take all of them. I’ll put them at 10,000.” He thought that was completely crazy, and that was the beginning of the M.A.D Gallery.

Treat people the way you want to be treated

We get this incredible amount of love at most of our launches, because on our platform, we’ve aggregated people who have got the same value as us. The journey is as important as the pieces. So the people who follow us, they follow the journey: they follow the interviews, they follow the reason why we do what we do.

The whole service and warranty that we’ve given at auctions has been something we’ve done for several years now, and of course it costs us money. Just the shipping is in the thousands of dollars for a watch. But it’s all based on one simple thing, and it’s to treat people the way you want to be treated. To somebody who is daring enough to put money on the table for one of our creations, I want to say thank you, and I want to reassure them that we’re here for them. Once you’ve come into the brand as a client, we try and service you the way I would like to be serviced as a collector. Because MB&F is not just a company, it’s not just a business; it’s my life.